On this page

Overview

The initial cases that prompt an outbreak investigation often represent a small fraction of the total number of people affected. Case finding is used to identify additional cases and determine who is at risk in order to:

- Understand the magnitude of the outbreak (including size and geographic distribution)

- Gather evidence about the source

- Allocate resources

- Refine outbreak case definitions

- Implement public health prevention and control measures (e.g., provide infection control advice or warn the public not to consume a particular food product).

The most effective case finding strategy will likely involve multiple methods and will vary depending on the circumstances of the outbreak. Case finding is an iterative process, and methodologies may change or evolve as more is known about the affected population.

Determining who is at risk

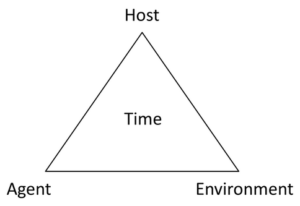

Gathering epidemiological information around what is known about the outbreak can define the case population and help determine suitable methods for case finding. The epidemiologic triangle is a helpful tool to define the elements of the outbreak and inform case finding methods and strategies.

Host (or person)

Are there characteristics of the initial cases that could inform who might be a case (or become a case) and how they can be reached? For example, the clinical spectrum of illness may provide information on where the individual will likely seek care and guide potential data sources to access, or if cases are employees of a particular organization, an employee list may be helpful. Other characteristics such as age and gender may also provide useful information, such as the use of age-appropriate tools (e.g., social media, online questionnaires).

Agent

Is the pathogen known? If so, how is the pathogen typically transmitted? For example, a pathogen that is most commonly associated with foodborne outbreaks may have large geographic distribution and may require a broad case finding strategy (e.g., communication across Canada). In a hepatitis A outbreak, which has post-exposure prophylaxis vaccination options, greater focus may be placed on contact tracing than for other pathogens. In addition, the pathogen may be known to affect a particular high-risk group (e.g., Listeria) or result in severe illness.

Environment (or place)

Are the initial cases linked by a place, such as a common event (e.g., mass gathering, sporting event, family dinner, wedding) or facility (e.g., long-term care facility, school)? Are they geographically diverse indicating that the geographic scope of case finding needs to be broad (e.g., communication messages to a wide audience to increase vigilance)?

Time

What is known about the potential period of exposure? This could inform the timing and urgency of case finding activities. For a hepatitis A outbreak, for example, there is a defined window for implementing post-exposure prophylaxis, which can impact when and how quickly case finding activities are initiated. In addition, what does the epidemic curve indicate (i.e., how are case symptom onset dates distributed over time)? A potential point source (group of people exposed to an agent from the same source over a brief time period) might, for example, help focus the case finding method to a particular common event that cases share.

Methods for case finding

After conducting an assessment of the outbreak, the case finding strategy may include a mixture of methods to maximize the number of cases identified, while balancing constraints, including public health resources. Before beginning, make sure there is a clear case definition and plan for public health action once additional cases are identified.

1. Routine case follow-up

As per routine case follow-up protocols, asking cases about other ill individuals or contacts can help identify additional cases. This method uses informal networks and can be particularly useful if there is a defined population (e.g., cruise ship, tour group).

2. Review existing data sources and/or implement new data collection methods

There are ranges of health and non-health data available for case finding. Some sources may be readily accessible (e.g., part of routine surveillance activities), or may be enhanced for the purpose of the outbreak investigation (e.g., increase frequency or timelines for reporting). In other situations, new data collection methods, such as accessing data sources that are not part of routine practice, can assist in case finding.

Examples of some health-related data sources include communicable disease surveillance and laboratory data. These sources may highlight other cases with a common pathogen that have been identified in a similar time period, but did not alert or trigger an outbreak investigation. In addition, cases may also present to other health care facilities, such as general practitioners, walk-in clinics, and emergency rooms, which may be a valuable source of information.

Non-health data sources can also be a rich source of information and often are related to population and event-specific characteristics. Some examples are:

- Company employees (e.g., employee directory)

- Travelers from defined groups (e.g., charter tour operators)

- Event participants (e.g., sport events)

- Guest lists (e.g., weddings, family gatherings)

- Restaurant reservation lists

- Hotel guest lists

- Credit card receipts (e.g., to identify individuals who may have dined at a particular establishment)

To initiate contact with the potential population at risk, there may be individuals or organizations that can provide access (or contact information) to reach these individuals. The method of contact will depend on the circumstances of the outbreak and may involve a variety of methods implemented in combination, such as telephone interviews, online questionnaires, and social media.

3. Targeted Communication

Communication is a useful strategy to increase vigilance and heighten awareness of an ongoing outbreak, in order to strengthen the identification and reporting of cases. The target audience can include the general public, front-line staff, and public health practitioners within the affected community and neighbouring jurisdictions.

Communications should contain general information about the outbreak and clear, specific action items being requested of the target audience (messaging may vary depending on the audience, such as the general public versus the medical community). Avoid ambiguity and technical jargon in these communications. Care should be taken not to divulge information that could compromise or bias the investigation, such as hinting at a suspected source. In jurisdictions with communications departments, engage your communications colleagues early on in the investigation to ensure consistent and effective messaging.

Some examples of communications include:

- Routine communication tools for reaching health care providers (e.g., newsletters, faxes)

- Public Health Alerts through the Canadian Network for Public Health Intelligence (CNPHI)

- Media (e.g., local television, radio, newspapers, websites, social media)

Limitations

Even under ideal circumstances, there are inherent limitations to finding all cases related to an outbreak. These include:

- Asymptomatic or subclinical infections that are not diagnosed

- Not all individuals will seek health care in the presence of illness

- Even if publicized in the media, not everyone may consider their illness associated with the outbreak

- Laboratory protocols may prevent the identification of cases meeting the case definition (e.g., laboratories that do not routinely do sub-typing will not be able to identify cases defined by sub-typing information)

- Population at risk not well defined or hard to find (e.g., no mechanism available to identify restaurant patrons, such as those paying cash)

- Resources (e.g., public health, acute care) may dictate the amount of effort that can be put toward case finding

- Access to case information (e.g., credit card billing details) may be subject to various privacy regulations that need to be taken into consideration

While efforts should be taken to maximize the number of cases identified, it is important to note that not all cases need to be identified to be able to characterize and understand the outbreak. However, the interpretation should take into consideration how the missed cases may affect the representativeness of the data. That is, if those cases are likely to be different enough to tell you something of relevance to the investigation (e.g., subgroup that may have different exposures).

Examples

- Case study, Module 2: Public Health Alert example

- Example: Case finding methods following a wedding banquet

- Using the media to find cases after potential hepatitis A exposure in Saskatchewan

Tools

Toolkit Public Health Alert (PHA) template

- This Microsoft Word document provides a suggested template for the content and layout of a Public health alert (PHA).

References

Torok, M. Case finding and line listing: A guide for investigators. FOCUS on Field Epidemiology, North Carolina Center for Public Health Preparedness. Available at: http://nciph.sph.unc.edu/focus/vol1/issue4/1-4CaseFinding_issue.pdf

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. EXCITE: Excellence in Curriculum Innovation through Teaching Epidemiology. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/careerpaths/k12teacherroadmap/index.html

MacDonald, P.D.M. 2011. Methods in Field Epidemiology. Jones & Bartlett Learning, USA.